Wine Basics

Wine Investing

Apr 24, 2025

The History of Investing in Bordeaux

For those unfamiliar with the concept, it may come as a surprise to learn that people have been investing in the wine of Bordeaux for hundreds of years.

As early as 1787, American statesman Thomas Jefferson noted in his diary that a premium was being charged for Bordeaux wines from the more mature 1783 vintage versus the more recent 1786.

The (supposed) Thomas Jefferson bottles – initialled Th.J

The lesson here – that fine wine improves with age, and will therefore be worth more in the future than it is today – remains the central pillar of wine investing.

Since Jefferson’s time, investing in wine has become an increasingly mainstream pursuit for investors seeking uncorrelated, attractive risk-adjusted returns.

This trend shows no sign of slowing, with HSBC reporting in 2023 that 96% of UK wealth managers expect allocations to fine wine to increase.

For many years, Bordeaux was the ‘only’ truly investment-grade region. Even as other regions like Burgundy, Champagne and Tuscany have emerged, Bordeaux retains a 30-40% share of secondary market trading volumes.

The History of Bordeaux

As perhaps the single most prestigious wine region, the history of wine-making in Bordeaux stretches back nearly 2,000 years.

Following Julius Caesar’s conquest of what was then Gaul, vines were planted to keep Roman legionary and native alike well-supplied.

As the Roman Empire expanded, what is now Bordeaux had easy access to an important shipping route to new colonies in Britannia – thanks to the favourable position of the Gironde estuary.

Roman Wine Amphorae

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, wine continued to be made – but almost entirely with ‘domestic’ consumption in mind.

In the 12th Century, the marriage of Henry Plantagenet (later King Henry II of England) to Eleanor of Aquitaine meant Bordeaux passing into English hands.

Unable to grow vines themselves, it did not take long for Britons to rediscover their love for what was quickly termed ‘claret’ – an English bastardisation of a Latin term used to describe ‘clear’ (e.g. light red or yellow) wines.

Even during the medieval period, export volumes from Bordeaux to the British Isles are astonishing. At the turn of the 14th century, a single Bordelais Town – Libourne – was exporting 11,000 tons of wine to London a year. The same area provided 1,152,000 bottles for the wedding of Edward II.

Libourne – Bordeaux

Trade disruption caused by the near constant wars between France and England in the centuries that followed meant that other export markets were sought.

In the seventeenth century, the arrival of Dutch engineers led to the draining of the marshland around the Médoc, and the planting of vines to make the sugary, sweet wine that appealed to Dutch palates – of which Chateau d’Yquem is the shining example. That meant that, in turn, Bordeaux wines flowed out through Dutch trade routes and across the world.

As tensions with France cooled following the Napoleonic Wars, the British Empire followed suit.

The enduring appeal of Bordeaux is much due to marketing. Savvy estate owners – notably those of Chateau Haut-Brion – realised the importance of developing a brand centuries before the term was in common use.

Amusingly, English diarist Samuel Pepys wrote on April 10, 1663 that he had ‘drank a sort of French wine called Ho Bryen that hath a good and most particular taste I never met with’. Realising the value of differentiating themselves, other Chateaux quickly built brands of their own.

A bottle of ‘Ho Bryen’ – as Samuel Pepys would call it

Bordeaux’s status as the premier wine region globally was enhanced in 1855, when Napoleon III ordered the wines of France to be ranked according to a classification system. The intention behind this was to ensure that only the finest were presented to a global audience at the 1855 Exposition Universelle de Paris.

The classification of the finest wines of Bordeaux wines into five separate categories, with four (later five) ‘First Growths’ – Premier Grand Crus – at the top and ‘Fifth Growths’ at the bottom, immediately inflated the prestige of those lucky enough to be included.

Interestingly, in what would be a harbinger for the emergence of wine as an asset class, the ‘price’ of the individual wines played a key factor in the selection criteria.

To this day, the first growths – Chateaux Latour, Lafite, Haut-Brion, Mouton and Margaux – remain amongst the most beloved by drinkers, collectors and investors, alike.

Enjoyed the article? Spread the news!

Read More

Wine Investing

14 Jan 2026

What Is En Primeur?

What Is En Primeur?

En primeur refers to the practice of buying wine before it has been bottled, while it is still ageing in barrel. Buyers commit capital today for wine that will only be delivered 12 to 24 months later, based on early tastings, critic assessments, and the reputation of the producer and vintage.

The system is most closely associated with Bordeaux, where it has operated at scale for decades, though variations exist in Burgundy, the Rhône and parts of Italy. While en primeur is often discussed as an investment opportunity, at its core it is simply a forward market for wine, a mechanism that allows wine to be priced and sold before it physically exists.

Whether that forward price represents value is the more important question.

Why En Primeur Developed

En primeur did not begin as an investment strategy. It emerged as a practical solution to a structural problem, cash flow.

Selling wine early allowed châteaux to finance operations, manage working capital, and reduce balance sheet risk. Merchants assumed the price risk and inventory burden, while buyers gained earlier access to sought after wines, occasionally at a discount for committing capital in advance.

As the market evolved, several shifts changed the character of the system. The introduction of standardised critic scoring created globally legible price signals. Demand became increasingly international, particularly from the US and Asia. Prices began to move well before wines were bottled, shipped, or consumed.

At that point, en primeur stopped being purely about financing production and became a mechanism for setting expectations.

How En Primeur Works in Practice

After harvest, wines enter barrel and remain there for up to two years. The following spring, critics and merchants taste unfinished samples during the annual en primeur tastings. Based on these assessments, châteaux release wines at a set price, typically in tranches, with volumes allocated to merchants.

Buyers who participate commit capital at this stage. Delivery takes place once the wine has been bottled and released, usually 12 to 24 months later.

During this period, buyers do not hold a liquid asset. They hold a claim on future delivery. That distinction is important, particularly from an investment perspective.

The Investment Case for En Primeur

When en primeur has worked well historically, it has done so for structural rather than speculative reasons.

The strongest performers tend to be wines with sufficient production to trade regularly, deep and established secondary markets, and release pricing that leaves room for appreciation once the wine becomes physical. In these cases, en primeur can provide access to wine at prices below long term fair value, particularly in undervalued vintages or periods of rising demand.

However, these conditions are not consistent. They depend heavily on pricing discipline at release and broader market sentiment.

Where En Primeur Often Falls Short

A common assumption is that buying early means buying cheaply. In practice, this is frequently untrue.

In recent years, many châteaux have priced wines to reflect anticipated future appreciation, rather than current market conditions. This shifts a significant portion of the upside from buyers to sellers and leaves little margin for error.

As a result, it has become increasingly common for wines to trade on the secondary market at or below their en primeur release price once they are physically available. This is not necessarily a failure of the wine itself, but a function of forward pricing in a market where sellers retain considerable influence.

Capital Lock Up and Opportunity Cost

Beyond price risk, en primeur carries meaningful capital considerations. Funds are committed for an extended period, with no yield and limited liquidity. Exit options prior to physical release are constrained, and pricing during this phase is highly sensitive to shifts in sentiment, macro conditions, and revised quality assessments.

These factors are often underemphasised in en primeur marketing, but they play a significant role in determining whether participation makes sense from a portfolio perspective.

En Primeur Versus the Physical Market

The key difference between en primeur and buying physical wine is timing.

En primeur requires investors to assume risk before information is complete. The physical market, by contrast, prices wine after quality has been realised, supply is known, and trading patterns are established.

Neither approach is inherently superior. They simply involve different risk profiles. The mistake is treating them as interchangeable.

How WineFi Approaches En Primeur

At WineFi, we do not treat en primeur as the default entry point for fine wine investment. We view it as situational.

Participation only makes sense when release prices sit clearly below observable fair value, liquidity pathways are well established, and the opportunity cost of capital is justified. In many cases, the secondary market offers more attractive risk adjusted entry points with greater flexibility and fewer assumptions.

En primeur is not where returns are automatically generated. It is where pricing errors occasionally occur.

Closing Thoughts

En primeur remains an important part of the fine wine market. It is not obsolete, nor is it inherently advantageous.

Used selectively and with discipline, it can play a role. Used reflexively, it often disappoints. Understanding en primeur, therefore, is less about learning how to buy early and more about knowing when waiting is the better decision.

That distinction is where long term outcomes are shaped.

Wine Investing

Wine Basics

14 Jan 2026

Who Is Robert Parker and Why He Matters

Robert Parker is an American wine critic best known as the founder of The Wine Advocate. Since the late 1970s, his writing and scoring have played a significant role in shaping how fine wine is evaluated, priced and traded, particularly at the upper end of the market.

For many investors and collectors, Parker’s influence is most visible through numbers. His use of the 100 point scoring system helped make wine quality easier to compare across producers, regions and vintages. Over time, those scores became embedded in the mechanics of the fine wine market itself.

Understanding Parker’s role is therefore less about personal taste and more about market structure.

The Wine Advocate and the Rise of Scoring

The Wine Advocate was launched in 1978 as an independent publication, initially focused on Bordeaux. At the time, much of wine criticism was opaque, relationship driven and difficult for international buyers to interpret.

Parker took a different approach. Wines were scored numerically and reviewed with a clear point of view. A single score could be read, understood and acted upon by buyers anywhere in the world.

This mattered because it reduced friction. Buyers no longer needed deep regional knowledge or direct access to merchants to form a view on quality. A score became a portable signal.

As the publication’s readership grew, so did the market’s sensitivity to those scores.

Parker’s Influence by Region

Parker’s impact was not uniform across the wine world.

He was particularly influential in Bordeaux, where en primeur pricing became closely tied to his early assessments. High scores often translated directly into higher release prices and stronger early secondary market demand.

His influence also extended into the Rhône, where he played a major role in elevating the global profile of producers such as Châteauneuf du Pape and Hermitage, and into parts of California, where his preferences aligned with richer, more powerful styles during the 1990s and early 2000s.

In regions where production volumes were sufficient to support secondary market trading, Parker’s scores became especially powerful price signals.

Parkerisation and Style Drift

As Parker’s influence grew, a phenomenon emerged that became known as Parkerisation.

Producers, consciously or not, began adjusting winemaking styles to appeal to the palate that appeared to score well. This often meant riper fruit, higher alcohol, more extraction and more new oak.

In some regions, this led to a degree of stylistic convergence. Wines became more homogeneous, at least at the top end of the market, as producers competed for critical recognition and the pricing power that came with it.

While this increased short term demand and visibility, it also sparked debate around diversity, regional identity and long term drinkability.

Parker and Other Critics

Parker did not invent numerical scoring, nor does he operate in isolation today.

Other critics and publications, including Wine Spectator, James Suckling, Vinous, Wine Enthusiast and Jancis Robinson, also use structured scoring systems, often on similar scales. Each has developed influence in different regions and market segments.

The key distinction is not the existence of scores, but how markets respond to them. Some critics have a measurable impact on price formation in certain regions. Others primarily influence consumer sentiment or short term demand.

The market has learned to differentiate.

Scores, Prices and the Price Per Point Effect

As scoring systems became embedded in the market, prices began to anchor not just to quality, but to quality relative to price.

One way this shows up is through price per point ratios. Two wines may receive the same score, but trade at very different prices. Conversely, some wines command significantly higher prices for relatively small differences in score.

This matters because scores are not linear in their economic impact. The difference between 94 and 96 points can have a disproportionate effect on demand and pricing, particularly in regions where critical opinion strongly influences buying behaviour.

Over time, markets tend to normalise these relationships. Wines that are expensive relative to their score often struggle to outperform unless scarcity or brand power compensates. Wines that offer strong scores relative to price tend to see more consistent demand and, in some cases, stronger price appreciation.

Understanding this dynamic is more useful than focusing on scores in isolation.

How Scores Behave Over Time

One important feature of critical opinion is that it evolves.

Wines are often rescored after bottling, and again after several years of ageing. Initial en primeur scores may be revised up or down as wines develop, and these revisions can influence price performance, particularly in the early years of a wine’s life.

However, the impact of rescoring varies by region and by critic. In some markets, early scores dominate pricing behaviour. In others, long term trading history matters more.

How WineFi Uses Critic Scores

At WineFi, critic scores are treated as inputs, not conclusions.

Our quantitative models incorporate both initial scores and subsequent rescores, but they are weighted based on observed influence on price performance within a given region. Critics are therefore weighted differently depending on where their opinions historically move prices.

We also analyse how scores relate to price through metrics such as price per point, allowing us to identify wines that are priced efficiently, aggressively, or attractively relative to their critical reception.

Scores are contextualised alongside liquidity, trading frequency, production scale and long term price data. No single score, or critic, determines an investment decision.

Closing Thoughts

Robert Parker’s significance lies in how he helped standardise the communication of quality at a global level.

By making wine easier to compare, he contributed to the development of deeper secondary markets and more transparent pricing. His influence also shaped production decisions and market dynamics, particularly in regions where trading activity was already emerging.

Today, Parker is one voice among many. His legacy, however, remains embedded in how fine wine is priced, traded and understood.

For investors, understanding that legacy is less about following scores and more about understanding how scores interact with price, liquidity and time.

Wine Investing

14 Jan 2026

Appellation Rules: What They Are and Why They Matter

Appellation rules are the legal frameworks that define where a wine comes from and, in many cases, how it is made. They determine what can appear on a label, which grapes may be used, how much wine can be produced, and the minimum standards a wine must meet to carry a regional name.

While appellations are often discussed in terms of tradition or quality, their real importance lies in how they shape supply, consistency, and long-term market behaviour.

What appellations actually do

At their core, appellations exist to protect origin. They ensure that a wine labelled from a specific place genuinely comes from that place, and that it meets agreed standards associated with that region.

Most systems regulate a combination of geography and method. This typically includes defined vineyard boundaries, permitted grape varieties, yield limits, and winemaking practices. These rules are enforced by regulatory bodies, and wines must meet formal criteria before they can use an appellation name.

This shared framework allows wines from different producers and vintages to be compared, traded, and valued across international markets.

The European model: origin and production combined

In much of Europe, appellations regulate not just where wine is made, but how it is made.

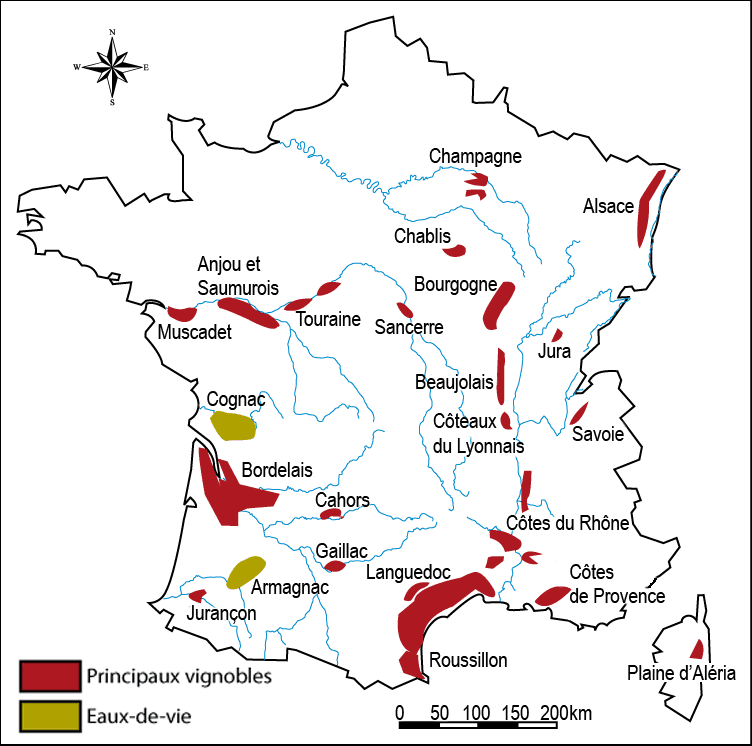

France operates under the AOC, or Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, now formally aligned with the EU’s AOP, Appellation d’Origine Protégée. These designations tightly define geographic boundaries and production rules, embedding scarcity directly into the system.

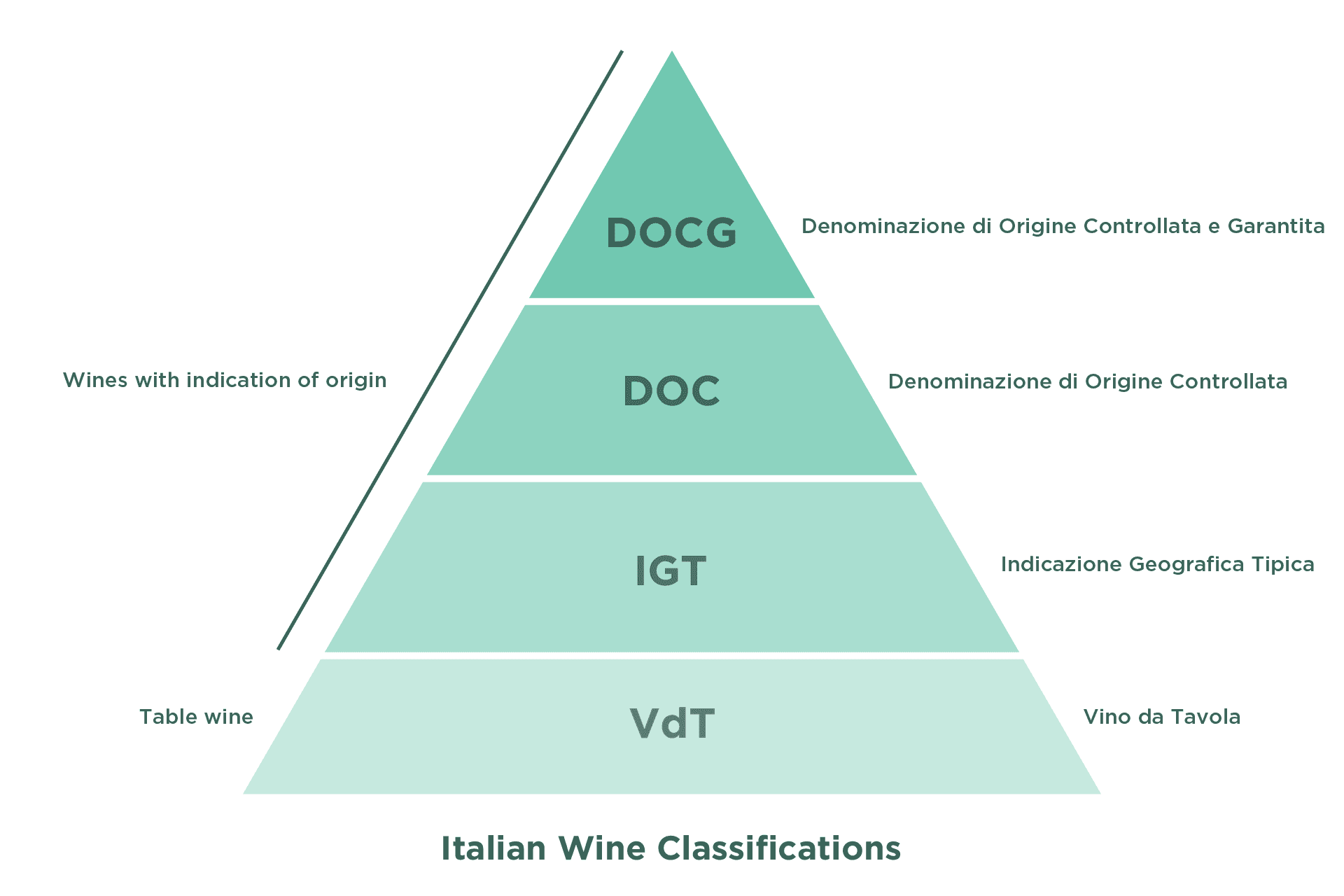

Italy uses a similar structure through DOC, Denominazione di Origine Controllata, with DOCG, Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita, representing the most strictly regulated tier. Spain applies DO and DOCa classifications, while Germany combines regional quality categories with its traditional Prädikat system, which historically focused on grape ripeness at harvest.

Across these countries, vineyard boundaries are fixed and yields are capped. When demand rises, producers cannot simply increase output. Prices, rather than supply, do the adjusting.

Flexible categories and innovation

Alongside these top-tier appellations, most European countries also offer broader designations. France’s IGP, Italy’s IGT, and Spain’s Vino de la Tierra allow greater flexibility in grape choice and winemaking while still indicating geographic origin.

These categories exist to give producers room to innovate outside rigid traditional rules. Some of the world’s most successful modern wines began life in these classifications before building enough reputation to stand on their own.

While appellation prestige remains important, the market ultimately prices reputation, consistency, and demand.

New World approaches: geography first

Outside Europe, appellation systems tend to be far less prescriptive.

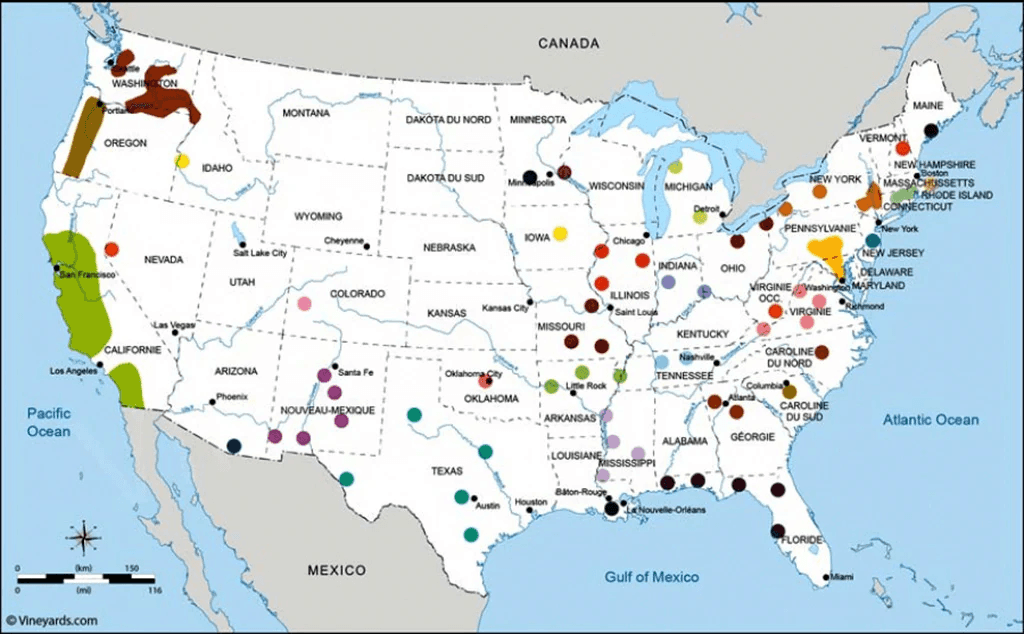

In the United States, American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) define geographic origin but impose few restrictions on grape varieties, yields, or winemaking techniques. A wine labelled with an AVA must source most of its grapes from that area, but stylistic decisions are largely left to the producer.

Australia follows a similar approach through its Geographical Indication (GI) system, focusing on accuracy of origin rather than mandated production methods. The United Kingdom applies PDO and PGI classifications, particularly for English sparkling wine, but again with relatively limited constraints.

These systems prioritise transparency over tradition. They allow producers to respond more freely to market demand, but they do not embed scarcity in the same way as Europe’s tightly regulated appellations.

Why appellation rules matter

Appellations shape more than labels. They influence how much wine can be made, how supply behaves over time, and how scarcity is maintained.

Regions with strict appellation rules and long-established reputations tend to show more stable pricing and deeper secondary market liquidity. Regions with looser frameworks often rely more heavily on producer brand strength to support long-term value.

For anyone looking to understand fine wine beyond consumption, appellations provide essential context. They are not guarantees of quality or performance, but they form the structural backbone of how wine is produced, traded, and priced globally.

In that sense, appellation rules are not just about tradition. They are one of the mechanisms that allow fine wine to function as a coherent international market at all.